Glasgow – the home of world sport?

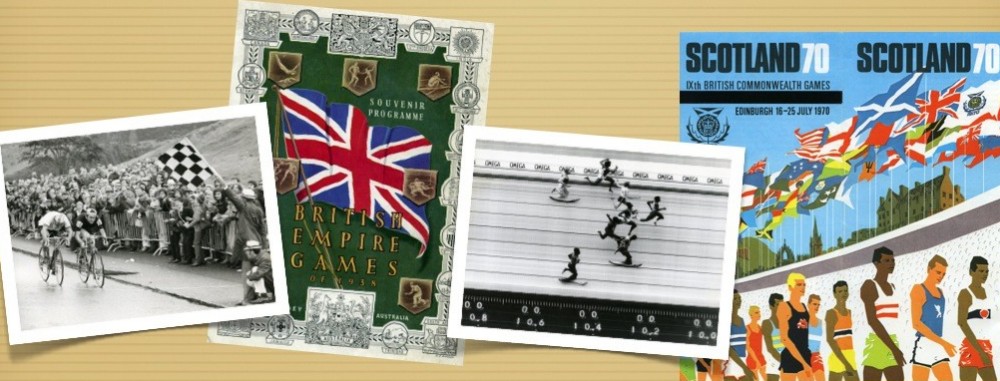

Glasgow, which will host the Commonwealth Games in 2014, is arguably one of the great historical centres of modern sport, not just in Scotland or the UK, but also the world. It is the historic centre of modern organised sports such as football, bowls and even shinty. Its reputation for sporting culture and its position at the heart of modern sports history reaches far and wide. Go in to the foyer of UEFA’s headquarters in Nyon, Switzerland, and there is a large aerial photograph of Hampden during the 1960 European Cup Final between Real Madrid and Eintract Frankfurt (above) which continues to be remembered as one of the greatest matches of all time. Glasgow is an iconic sporting city. Its sporting culture has a special place in our cultural history and, therefore, in our cultural heritage.

My interest in sport in Glasgow stems from a broader interest in the relationships between the media and sport. Two great wings of 19th and 20th century popular culture which for more than a century have conjoined to form an inseparable bond – what many have called a ‘symbiotic relationship’. This relationship has a very long history – from early pamphlets and forms of sports journalism, to early experiments in film (many using boxing), to radio, television, the Internet and now all manner of mobile devices and electronic games.

Why is this important? Sport provides the media with a ready-made audience, it has value for advertisers, media commerce or in the case of the BBC, public justification for funding. The media provides sport with exposure to a wider audience, it also provides pathways to revenue through broadcasting rights and sponsorship income. In the contemporary sports-media world, we are very familiar with this, but we might not be as aware of how these relationships began and were played out in popular culture in the past. This is particularly true of more localised media. For example, sport features prominently in Glasgow based newspapers such as the Daily Record or Evening Times, which were preceded by Glasgow-based sports journals such as the Scottish Umpire, Scottish Athletic Journal and Scottish Sport the origins of Scottish sports journalism (featured right).

My previous research on the history of sports broadcasting, exploring the BBC archives to understand how it developed its sports coverage and developed the codes, conventions and practices of first radio and then TV sport (see my article on broadcasting the 1948 Olympic Games). Less well known, or researched, is the important role that film and the cinema played in the early half of the Twentieth Century in the development of sport, and in fostering a wider interest in sports spectatorship and fandom, and also how sport was a key content for newsreels. As part of my current sports heritage project in Glasgow I want to explore this relationship a little further, and to use sport in the southside of the city, its sporting cultures, sporting places, and historical events, as a way in to understanding why looking at this material – our heritage – is of value to today’s sporting culture, and our wider sense of community more generally. If city heritage means anything, I would suggest it is the value it provides in educating people and communities about their past, their present and informing their possible futures.

Why Take Sports Heritage Seriously?

Studying sport is partially about celebrating sporting practice and achievements – but it is much more than that. It also tells us about who we are, our identities and how we form them. Some of these have very powerful symbolic meanings – and in Glasgow, in the context of football, there is no need to search too far to find illustrations of intense emotional and cultural ties to particular clubs and their meaning.

There are other themes to explore too:

1. Then and now – The continuities and changes that occur in Glasgow sports cultures and sportscapes. What can sport on film reveal about our knowledge and understanding of the past? What does it tell us about our present sporting environment?

2. Where and how sport is played – Film offers us a snapshot of sporting behaviour on and off the field of play. Intricate analysis of film could enable a wider understanding of how a particular sport was played: how rules and laws of sport have changed and were interpreted, the extent of violent play and its connection with masculinity, the place of women in sport, the evolution of sporting techniques and modes of performance through sport. Further, it illuminates stadium architecture and the use of advertising, and the emergent forms of spectatorship and fandom. Indeed, all the requisite aspects of understanding the place of sport in society can be analysed and interpreted through sport on film.

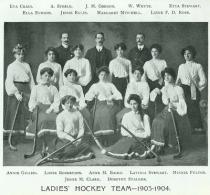

3. That women played and watched sport, and always have done, but with particular patriarchal conditions attached, many based on physiological myths, and out and out prejudice. Glasgow women have played sport in significant numbers since the late 19th century. Finding out what sports attracted female participants and spectators, how this fitted in with everyday life in Glasgow for particular women, and perhaps excluded others, are all interesting themes to explore in terms of sports history and heritage.

4. Other sports than football – That sport doesn’t simply mean football – there are other sports as well. Football dominates our media landscape like never before. With the exception of rugby internationals, it is the only sport to regularly draw large numbers of spectators. Many of the films made in the first half of the 20th century reveal a wide range of sporting pastimes, some with surprisingly large following. The preponderance of bowling clubs, especially in the south of the city, is one example, and some sports, such as motorsport, were just emerging. Film provides a way in to experiencing these sports and seeing just how popular they were.

5. Hidden/Forgotten Sporting Places – That our urban infrastructure is littered with sporting places, formal and informal, some of which have survived and flourished, and others that are masked from our immediate view, have become faded memories and have disappeared from public consciousness. There is more awareness than ever before about our cityscapes and how they have changed over time. The role of sport in these changes is fundamental to learning and understanding our urban environment. This is particularly true where sports venues and clubs no longer exist.

6. The idea of the club – and what that means for communities – is also a fascinating theme running through much of Glaswegian popular culture, which is often underplayed or ignored as important to our connections with social history. Perhaps only at times of crisis – as in the malaise at Rangers – do we begin to take stock of what clubs and sporting institutions mean to communities, for better or worse. This aspect of sporting heritage is fundamentally about people, how they organised themselves around their enthusiasms, and how they built sporting legacies, in quite localised ways, for us today.

Film and Sport

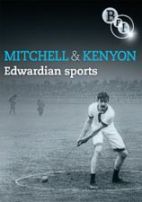

The sporting themes I mentioned emerge in abundance in an important repository of our popular culture – film. We should never underestimate the importance of film to a society, both as a creative medium, but also as a communicative form that has captured our past and forms a key bridging point to our heritage. The visual turn in historical studies has led to increased public and academic interest in the moving image. Early film archives have recently facilitated terrestrial television programmes such as The Lost World of Mitchell and Kenyon or The First World War in Colour. Film is increasingly of interest to historians of the modern period, and general film and cinema history already has a substantial focus. I plan to provide some examples of what I mean by this, drawing on the sporting themes around Glasgow sport I mentioned. But if you go away tonight with one piece of information or insight, it would be to connect with the film heritage that is now at your fingertips online, in the digital repository of the Internet. It is a very exciting resource, and very interesting time to explore heritage themes in this digital environment. We are only just beginning to realise the power of digital communication to connect with and understand our past and its heritage value. The resource is immense, both in access to information, but also the ability to connect with other people and groups in new and interesting ways.

What kind of films?

1. Local Topicals

The 1895 Boat Race and the Derby were amongst the very first events shot by early British filmmakers such as Paul and Acres. The ‘Mitchell and Kenyon’ BFI archive is of immense value and has shed light on lost details of particular sporting occasions, key athletes and teams, the evolving codification of sport and the behaviour of sports spectators from 1901 to 1907. The ‘Mitchell and Kenyon’ archives have proven a boon to film and sports historians alike and are highly suggestive of the rich sporting cultures that existed in Edwardian Britain. Sport was key in attracting audiences to the burgeoning trade of travelling exhibitors of cinematography in the formative era of the film industry. It is clear from preliminary research in the UK’s regional archives, including Glasgow, that many other filmmakers were covering sporting occasions at the same period and beyond. Local topicals, which were immensely popular in Glasgow and Scotland more broadly, typically featured outdoor events that attracted local people to the cinema. They were clearly influenced by the travelling films of Mitchell & Kenyon, and sporting events formed an important function in this respect. Exhibitors used the locally contracted films, which were traditionally much longer than newsreels, to show people themselves, and many of these films featured sport as the main attraction. The topicals were often exclusive to a particular cinema. Their characteristics are very similar to Mitchell and Kenyon’s footage, including panning shots of the crowd, a feature later to be picked up by the newsreels.

2. Newsreels

Sport had featured in the earliest moving images produced in the late-1890s and by the inter-war period sport was crucial to cinema newsreels. Newsreels were the short topical news items, usually with a whimsical, entertainment value, that preceded the main feature. They reached millions of people, particularly in Glasgow where in 1939 Glaswegians went to the cinema an average 51 times a year (compared to a national average of 35). Indeed, it has been argued that by the 1930s sport obtained its first mass audience through the newsreel, cementing the popularity of spectator sport in a wider national consciousness. The various companies, from French-owned Gaumont to American-owned Universal and Paramount, all covered women’s sports too, telling us much about leisure, sport, popular culture and the constructions of femininity during a significant period. Newsreels would help foster a new appetite for the visual representation of sport and capitalise on its commercial value – something television would ultimately usurp and turn in to a global love-match, we see this week with the Olympic Games.

3. Amateur Film

Amateur film enthusiasts, particularly of the late 1930s through to the 1960s are invaluable sources of highly personalised, archive footage. Amateur film footage of sport may also include images of local organised sport, but more frequently captured the informal sporting pastimes of families, schools and local communities that show sport in both public and private domains. To own a film camera in this era was a sign of relative wealth, and many enthusiasts were members of film clubs and society’s who shared techniques and collectively screened their films.

4. Documentary Film

Instructional fitness films inspired by the documentary movement were made throughout the 1930’s, 40’s and 50’s.

The documentary movement began in Scotland in the inter-war years led by John Greirson, who was born in Deanston, Perthshire. Grierson introduced a strong social commitment in to factual film-making, and his influence on what he termed documentary has been immense. As a director and producer he led the film units of the Empire Marketing Board and the GPO in the 1930s, and established the Films of Scotland Committee. His work influenced a number of promotional documentaries on Scottish sport, including Sport in Scotland (1938) and Scotland For Fitness (1938), which were both part of a series made for the Empire Exhibition of 1938; and 4 and 20 Fit Girls, a wartime instructional film for women’s fitness. Another important dimension to sport documentaries national identity. Sport clearly plays an important role in the formation of regional and national identities. The secular rituals of sport and the civic pride it frequently stirs in particular communities is of great interest to both social scientists and historians. Film offers a way in to understanding the dynamics of how these identities are constructed. Here, the context that connects filmmaker, subject matter and the audience are all-important.